Everything Publishers Need to Know About URLs

From the HTTPS protocol to a publisher's domain name all the way to the (lack of a) trailing slash, every part of a webpage's URL plays a role.

This is a long one, so grab your favourite beverage and settle in. Everything that follows is based on my own experiences and opinions, so don’t take it as SEO gospel. I’m just one dude bleating into the void.

Whether you work in tech/product or audience growth or editorial, the topic of URLs tends to come up regularly. What’s the best URL for an article? Does having a date in the URL matter? How do we create optimal URLs for sections and tags? Can we change our (sub)domain? Common questions publishers want easy answers to.

In this edition of SEO for Google News I’ll be looking at (almost) everything relating to URLs. From the HTTP(S) protocol to your domain name and subdomain, to the naming conventions for your sections and folders, all the way to individual article URLs and whether or not you use a trailing slash; I’ll discuss every part and explain what impact it may have on your site’s SEO.

Spoiler alert: optimised URLs play only a small part in an article’s ranking in any Google vertical.

It used to be the case that keywords in URLs helped pages perform better. Nowadays, keywords in URLs are a small ranking factor, massively outweighed by on-page content factors.

Now, with that out of the way, let’s talk URLs.

What is a URL?

A URL is the web address for a resource. That resource can be a webpage, an image, a JavaScript file, etc. If it can be accessed via the web, it has a URL.

A URL is made up of several components. It starts with the scheme, which is usually ‘https://’ these days. That means it’s a web resource served over the HTTP protocol with encryption enabled.

Then we get the domain name - www.example.com - which itself consists of three components:

Subdomain: this is common but optional. Most sites will use the ‘www’ subdomain, but many sites don’t have a subdomain at all and only use the 2nd and top-level domains.

I.e. techcrunch.com doesn’t use a subdomain, whereas news.google.com is a subdomain of google.com.

2nd-level domain: this is the main part of the domain name, and is usually mentioned in the same breath as the top-level domain when we refer to websites. We’d always say ‘CNN dot com’ when we talk about the CNN website.

Top-level domain: this last part of the domain name historically referred to the type of organisation (.com for commercial, .org for organisations, etc.) and/or the country the domain is associated with (.co.uk for commercial businesses in the United Kingdom, .nl for every Dutch website, etc.)

Nowadays top-level domains are not indicative of business types, though often still very much relevant for the country your site is assumed to target. More on that later.

After the domain we have the path of the web resource, which usually consists of a directory (also known as a folder) and sometimes ends in a filename.

Sometimes URLs can also contain parameters, which are indicated by a question mark followed by whatever the parameter is.

Rather than dig into the precise details of all the technical specifics of every aspect of a URL and retreading ground others have so thoroughly plodded already, I’ll just link to this excellent article on the Mozilla site that explains it all in agonising detail.

Scheme: HTTP vs HTTPS

The first question that arises is what scheme you should use? And the answer is simple: HTTPS.

The difference between HTTP and HTTPS is one of security. A website serving over HTTP:// sends its data over the web in unencrypted, plain-text form, which means it can be intercepted and read by nefarious actors.

With HTTPS, the data is encrypted before sent across the web to the recipient, where it is then unencrypted. Any data intercepted as it crosses the web is encrypted gibberish. This makes the communication between the website and the recipient more secure.

In 2022, almost all websites are served over HTTPS. Back in 2014 Google began a major push for websites to adopt HTTPS, making it a (small) ranking factor.

Now that pretty much all websites use HTTPS, that ranking factor is almost meaningless. HTTPS should be the default for your website. If your site is still on HTTP, you’re basically living in the pre-historic caveman web.

HTTP/2?

Now, you may have heard of a thing called HTTP/2. This is the next version of the HTTP protocol. For most of the web’s existence, we’ve been using version 1.1 of the HTTP protocol, and it was time for an upgrade.

The HTTP/2 protocol is a bit faster than HTTP/1.1, with a webpage’s resources being requested in bulk rather than sequentially.

Many websites are already using HTTP/2. Google has started crawling with HTTP/2, though it’s important to note that this doesn’t give your website any ranking advantage.

At best, adopting HTTP/2 may give your website a small crawl rate improvement, as it’ll be a bit faster and efficient for Googlebot to crawl your site.

Domain Names

A news publisher’s domain name is more than just a brand. Your domain name sends strong signals for targeting and relevancy.

Contrary to popular belief, you don’t need to have specific keywords in your domain name anymore. ‘AwesomeRugbyNews.com’ isn’t going to rank better for ‘rugby news’ for having those words in the domain. That used to be the case in the prehistoric web, but it hasn’t been a factor for many years now.

But there are two crucial components of your domain that determine your success in Google News: the top-level domain (TLD) and the subdomain.

TLD & Geotargeting

When you use a generic TLD like .com or .info, Google will assume you’re not targeting a specific country. You can nonetheless tell Google your content is intended for a specific country; in Google Search Console, in the International Targeting section, you can set a specific country to target.

If this is not configured, Google will not assume your content is aimed at a specific country. It may still conclude your content is geotargeted by looking at other clues, such as your content’s language, folder structure, hreflang references, etc.

When you use a country-code top-level domain (ccTLD) such as .mx or .co.uk, Google will always assume your content is primarily aimed at users in that country. It won’t entirely prevent your site from ranking in other countries, but it does strongly hinder your ability to rank outside of your targeted country’s Google version.

Some exceptions to this are ccTLDs that are commonly used as generic TLDs, so Google doesn’t assume any geotargeting there. An example would be the .ms ccTLD, which is Montserrat’s country-code domain but is used so often outside Montserrat that Google doesn’t assume any geotargeting.

If you want to check whether a TLD is considered generic or country-specific, Google maintains a list of TLDs it considers to be generic.

Subdomains

Whether you use a subdomain or not is irrelevant for SEO. Google doesn’t care whether you’re www.publisher.com or news.publisher.com or just publisher.com.

What Google does care about is consistency.

Inclusion in Google’s news ecosystem (itself a controversial topic these days) is based on your full domain name, also called the ‘hostname’.

For Google, www.example.com is a different website than example.com. If you’re currently included in Google News with your www.example.com website, and you decide to change your site structure and move your news content to news.example.com, you’ve basically changed domain names.

This means you lose your Google News inclusion.

Even with 301-redirects in place and a Change of Address notification, inclusion in Google News for your changed domain is unlikely.

Whenever I’ve seen publishers change any part of their domain name - whether it’s just the subdomain or a complete domain change - they always lose their Google News traffic (and, by extension, their Top Stories traffic).

This traffic doesn’t bounce back; at best they will get some sporadic bursts of Google News traffic, but nothing substantial.

When they then revert the domain change and go back to the old domain, usually we see the Google News traffic come right back.

So the lesson is clear: if you’re currently getting good traffic from Google News and Top Stories, don’t change any part of your domain name.

Folders

Folders (AKA directories) are used to categorise your content into sections and subsections. Typically a section name, like Sport, is directly referenced in the folder name: /sport/.

It is important to use folder names that accurately capture the section’s contents. The URL of the folder should reflect the folder’s topic. So don’t call a folder /sport/ and then use it to collect articles about the weather; if it’s called /sport/, it should contain sport-related stories.

Google wants your section URLs to be static. So when you have a section on /sport/, don’t change that to /sports/. Keep it as-is, because Google uses your section pages for discovering newly published content.

Even with redirects in place, changing your section page URLs can lead to a dramatic drop-off in crawl rate and indexing on your site until Google comes to grips with your new URLs (which might take a while). So don’t change section URLs unless you really need to.

Folder Hierarchy is Optional

When you create a subsection that is a part of a bigger section - for example Rugby under Sport - should you create the /rugby/ folder under the /sport/ folder, so you get /sport/rugby/?

Or can you just use /rugby/ as a folder under the domain, without any parent-child relationship?

The answer is: for SEO, the difference is minimal.

Including folder names in the URL can help Google identify relevant entities that apply to the section, but there doesn’t need to be a hierarchical relationship.

Personally, I prefer hierarchical folders (example.com/sport/rugby/), but you can also use root folders for every section and subsection on your site (example.com/sport/ and example.com/rugby/). The hierarchy of the folder can serve a user experience purpose, but it doesn’t help or hinder your SEO in a significant way.

The main factors determining the SEO value of a given (sub)section are the section name (specifically the <h1> heading and meta <title> tag) and internal linking.

The section name should be reflected in the page heading and <title> tag, so that Google understands what topic the listed articles share.

When a subsection like Rugby is part of your site’s top navigation - ideally as part of a set of contextual subnavigation links under the Sport top nav heading - then the URL of the subsection is irrelevant. Whether it’s /sport/rugby/ or just /rugby/, the prominence of the ‘Rugby’ link in your top navigation is what really matters.

In a Google Webmaster Hangout, John Mueller stated that click depth is what matters and not the actual folder structure of the URL.

I’ll be digging into internal linking in an upcoming edition of this newsletter, as it’s a complex topic with a lot of nuance that’s worth exploring in detail.

Article URLs

So, what makes for a perfectly optimised article URL? I get so many questions about this, so I’ll tackle the most common ones in turn:

Do article URLs need dates in them?

No. If you currently use dates in your article URLs (like theguardian.com does), you don’t need to remove them. It’s fine to have them, but there may be a small downside with regards to evergreen content that you want to rank beyond the news cycle; Google doesn’t care about the date in your URL, but your audience might notice them and recognise potentially outdated content.

But that’s a small risk, as the on-page ‘published’ or ‘last changed’ date is more likely to be noticed. For Google this visual date, combined with the ‘dateModified’ attribute in your NewsArticle structured data and the <lastmod> attribute in your XML sitemaps, play a much bigger role. The date in the URL is negligible.

There is an advantage to having dates in your URLs; it’s much less likely you’ll ever create a duplicate article URL. When you cover the same type of story regularly (like a sports event between two teams that compete every season), the date in the URL prevents you from inadvertently recreating an existing URL for a newer article.

Should article URLs have a folder structure?

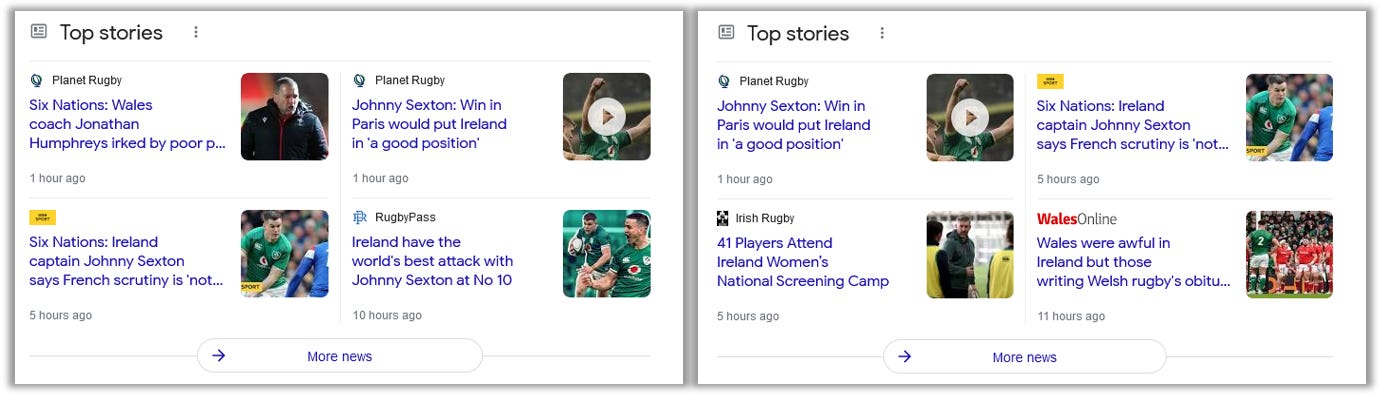

This is optional, but it might help. Google likes to see relevant entities that are mentioned in an article reflected in the URL. Sticking with the Rugby example, if you write a story about the Ireland national rugby team then it helps to have the words ‘rugby’ and ‘ireland’ in the article URL.

Whether this is in the form of (sub)folders or as part of the article filename (also known as the ‘slug’) doesn’t matter, as long as it’s in the full article URL.

So for Google, all of these are fine:

example.com/ireland-defeat-wales-six-nations-rugby

example.com/rugby/ireland-defeat-wales-six-nations

example.com/rugby/ireland/wales-defeated-six-nations

Keep in mind that these days Google is very good at understanding synonyms. ‘Ireland rugby’ and ‘Irish rugby’ are pretty much identical as far as Google is concerned.

You can easily test this: simply search Google for the two phrasings, and you’re likely to see very similar results in both the regular SERPs and the Top Stories carousels.

There can be some subtle differences, as changed phrasing could mean a slight variation in search intent . And some websites have stronger on-page optimisation for alternative phrasings. Generally though, you’ll see a great deal of overlap in what Google shows for slightly different wordings that mean the same thing.

Can the URL be different from the headline?

Yep, as long as they convey the same meaning. Your URL can be an exact copy of the article headline, or it can be an entirely different phrasing of the same general message.

But the URL and headline should match thematically. The headline serves a topical purpose: it signposts the contents of the article. The URL serves the same purpose.

Sticking with my earlier example, for an article with this URL, both of the following are perfectly acceptable headlines:

URL: /ireland-defeat-wales-six-nations-opener/

✅ Headline: Ireland Defeat Wales in Six Nations Opener

✅ Headline: Conway and Hansen Star as Wales Suffer Thumping Defeat by Rampant Irish Rugby Side

For the purpose of matching URL and headline, either are fine. The second headline is probably better for SEO, as it contains more relevant keywords (i.e. player names) and with 82 characters it makes better use of the space allowed in Google’s news rankings than the shorter headline.

Can you use special characters in a URL?

Short answer; yes, but you shouldn’t.

Long answer; special characters are often processed just fine, but sometimes can lead to issues when a character needs to be encoded or is otherwise not easily parsed. It ’s better to keep things simple and stick to basic characters. Use the standard alphabet and limit your non-text characters to hyphens and slashes.

For word separators, hyphens are recommended. Avoid special characters that could result in encoded URLs (that’s when you see those numeric strings with the percentage symbol).

Accented text is usually fine, though some uncommon accented characters can also result in encoding which may break the URL in some platforms. If you want to be 100% safe, just use the character’s unaccented version.

The URL should not contain quote marks, parentheses, exclamation marks, question marks, or any other special characters that may exist in an article headline. Just omit those entirely from the URL.

Is capitalisation okay?

This is one of those grey areas where you’ll want to keep things as simple as possible. For Google, a capital letter is a different character than the lowercase version.

So /Irish-Rugby/ is a different page, as far as Google is concerned, from /irish-rugby/. If your website serves identical content on both of these URLs, you may be creating duplicate content challenges for yourself.

It’s best to stick to one format - usually all lowercase - and don’t allow any capitalisation in URLs. Many tech stacks are configured to default to lowercase, but some platforms (looking at you, Microsoft), allow and even encourage capitalisation in URLs. This is generally a bad idea.

Just stick to lowercase in your URLs.

What about file extensions like .html?

This question can be relevant if you have a website that still uses extensions like .php or .html at the end of a webpage URL.

Modern web technology doesn’t require file extensions anymore. Whether your article ends in .html or with a slash (which, technically, makes it a folder), or ends without any notation at all - it really doesn’t matter. All those URL patterns work, and they can all perform just as well in Google.

The only caveat to note here is that consistency matters. If you have an article that can be accessed on .html as well as without .html, then you’re basically creating duplicate content issues.

The same applies with trailing slashes. These two URLs are in effect two different pages, as far as Google is concerned:

example.com/rugby/ireland-defeat-wales-six-nations

example.com/rugby/ireland-defeat-wales-six-nations/

The trailing slash makes the URL different and will cause Google to treat it as a separate article.

A simple rel=canonical tag isn’t really sufficient to address such duplication. Whether you use .html, or trailing slashes, or nothing at all, doesn’t matter for SEO; Google treats them all equally.

But you’ll always want to implement automatic redirects from your non-preferred version to the preferred version or serve a 404 Not Found error on the non-preferred version of the URL.

And your internal links and XML sitemaps should always reference your preferred URLs, and only the preferred URLs.

Can you use parameters in article URLs?

You can, but you shouldn’t. In its Publisher Center documentation concerning redirects, Google specifically advises against using the ‘?id=’ parameter in your article URLs.

Now this is in relation to redirects, but the same concept may apply to URLs across Google’s news ecosystem. While URLs with parameters can be crawled and indexed, and often rank fine, I feel they’re just not particularly useful.

Parameter URLs are often less keyword-rich and more convoluted. For me, there are no advantages for parameters in your article URLs, and only disadvantages.

A publishing site that uses URLs with parameters is often the sign of an outdated technology stack. The parameters aren’t necessarily the problem themselves, but they point at development approaches that are simply not conducive to building well-performing optimised websites.

In ecommerce I’m much more forgiving of URL parameters, as they can serve an important purpose for navigation and filtering.

In news, however, it’s hard to think of a use case where parameters add anything of value - and easy to think of instances where parameters add unnecessary complexity and points of failure.

So, as a rule, avoid using parameters in your article URLs.

Do my article URLs need a unique ID?

No. This is a leftover from the early days of Google News, when there was an explicit requirement for article URLs to contain a unique ID number that was at least 3 digits long.

Google dropped that requirement many years ago, as its news indexing system became more advanced (and in 2019 merged with its regular crawling and indexing systems). So you don’t need unique ID codes in your article URLs anymore.

If your tech stack still automatically creates ID codes for your articles in their URLs, you don’t need to change it. The ID codes don’t add anything, but they don’t hurt either.

How long should my URL be?

As long as you want, up to the rather extreme 2048-character limit built into most browsers. There’s little correlation between URL length and article performance in Google’s news ecosystem.

Generally I prefer somewhat shorter URLs, but that’s mainly for usability reasons. I tend to recommend removing stop words from URL slugs, so I’d prefer to have:

/ireland-defeat-wales-six-nations-opener

Rather than

/ireland-defeat-wales-in-six-nations-opener

But the differences are marginal and for SEO it doesn’t really matter. Whether your article URL is 50 characters or 200 characters, Google will rank it just fine.

Should You Change URLs?

As I said near the start, a URL is the address for a web resource. For news articles, the URL is the unique identifier that Google uses to decide whether the page should be crawled or not.

If a new URL is different from an already existing URL, even just one character different, Google will initially interpret it as a new page that should be crawled and indexed.

This is why changing URLs is such a contentious tactic. When you change an article’s URL after the article has been crawled and indexed, you are basically creating an entirely new article.

It can be an entirely valid thing to do; when the article contents have changed sufficiently that it warrants a new story, you change the headline and republish it with a new URL. It’ll get treated as a new article, and will rank independently from the original piece.

In those cases, the old URL should 301-redirect to the new one. This allows Google to canonicalise the ranking signals on the new URL, and prevent you from ranking with an outdated news story.

But that is one of the few contexts in which changing URLs is a good thing. For almost any other purpose, changing existing URLs is generally a Bad Idea.

The Problem With Changing URLs

When you change a page’s URL, you are effectively creating a new page. That page then needs to be crawled, indexed, and evaluated in Google’s complex systems to determine what - if anything - it should rank for.

Even with redirects in place, the consolidation of ranking signals on the new URL is not a perfect transfer. A page URL that has been around for many years can have accumulated a lot of historic ranking signals, such as old links from other websites.

When you change the URL and create a new page for Google to rank, those historic ranking signals may not transfer to the new URL. Google may need to crawl those old links again before their value is associated with the new URL through the redirect - and it may not ever do that. Or, even when Google recrawls those old links, the ranking value of those links will be diminished because they’re from older articles that have now descended deep into the linking site’s archive.

And then there’s a theory that some measure of PageRank (or link equity, or whatever you want to call it) is lost in a redirect. Over the years Google has given conflicting information about this, though recently they seem to have standardised on “no link value is lost in a redirect” which I’ll admit I’m a little skeptical of.

Regardless, the advice is the same: don’t change URLs for any piece of indexed content unless you have a damn good reason to.

This is why site migrations are such a trepidatious enterprise. Changing a site’s tech stack often means changing page URLs, which can cause all sorts of SEO problems especially for news publishers.

URLs and Ranking

URLs are endless food for discussion, but in the end everyone wants to know how big of a ranking factor they really are. In my experience, URLs are only a small ranking factor, well down on the list.

For articles, I consider these to be the pivotal news-specific ranking factors, listed in order of importance:

Article headline

Article content & quality

Featured image size & aspect ratio

Article categorisation

Average article Core Web Vitals scores

Website E-A-T factors

Article URL

Meta <title>

I rate the URL as a pretty low ranking factor. Admittedly, this would be a very different list for regular, non-news ranking factors. But for news, the article URL is low priority so don’t spend too much effort on perfecting it.

I hope this edition of my newsletter has helped answer some questions you may have about URLs. If there’s anything more you want to know about URLs, please leave a comment and I’ll do my best to provide a useful answer.

Miscellanea

Some interesting bits and pieces I’ve come across the last few weeks:

The folks at NewzDash now have public lists of the Top 100 News Publishers in 22 countries in terms of Google News & Top Stories visibility, which are continuously updated. A great resource to add to your bookmarks!

A study by PressGazette shows that WordPress is by far the most popular CMS for publishers. It should be noted that niche CMSes like Glide aren’t recognised in this study, so they’d show up as ‘home made’.

There’s a new API for Google Search Console, which allows you to do bulk ‘Inspect URL’ queries. Bloody useful for getting relevant crawl & indexing data out of Search Console for up to 2k URLs per day per verified property.

Because we don’t have enough meta tags yet, Google has introduced the

indexifembeddedmeta tag that can help content syndicators get their embedded content into Google.

Dan Smullen wrote an excellent piece on how to use tagging for maximum SEO value. He digs into the specifics for news publishers in the article’s 2nd half.

What happened when Search Engine Land turned off their AMP articles? Nothing. More nails in the AMP coffin.

The Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism have released a mammoth piece predicting 2022 trends for journalism, media, and tech.

The folks at Chartbeat published their list of the most engaging stories published in 2021 in the US. It’s an interesting list, dominated by the major political events of the year.

The HTTP Archive has created a data studio dashboard showing the Core Web Vitals scores for websites that use different technologies. Fascinating data, worth playing around with to see how various tech stacks perform.

That’s it for this edition of SEO for Google News. Apologies for the long wait, this piece took me a while to get right (and I’m still not entirely happy with it, but hey).

As always, thanks for reading and subscribing, and hopefully I’ll get the next one done a lot quicker.

This is an amzing read, Thank you for your time.

Hi Thanks for shearing this google news its my website https"//devquiretimes.com and its about news how to add this website in google news list